Reflections on Found Lake – By Peter B. Mills

The Algonquin Art Centre is hosting a special solo exhibit, “Found Lake: The Works of Peter B. Mills” on display from Sept 1st – October 21st, 2018. Peter was our 2017 artist-in-residence, and in preparation for the 2018 show wrote a series of “Reflections on Found Lake” during his residency, reflecting on his time in the Algonquin both as a Park naturalist and as an artist. To view Peter’s recent artwork, click HERE

“Reflections on Found Lake”

By Peter B. Mills

Found Lake again, and a return to my old haunts. I stand in the lake submerged to the waist, my feet sunken in muck up to my ankles. I have a firm grip on the handle of my net, which I have cocked back behind my right shoulder. I shift my weight from foot to foot; I have been positioned here for nearly twenty minutes and it is getting cold. I hear the voice of a passerby call out to me from shore:

“What’s the net for?”

“Dragonflies”, I answer.

“Oh…ok”.

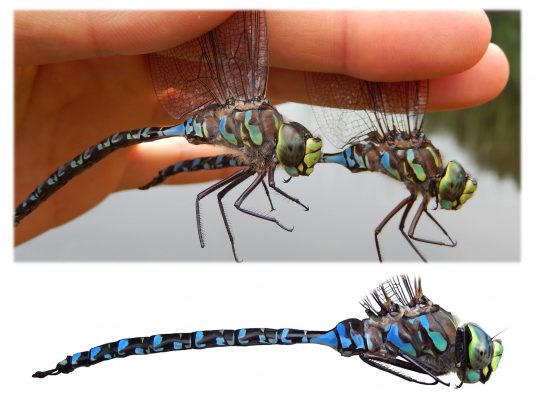

My tenure in Algonquin Park took a decidedly entomological focus, and dragonflies were my primary muse. I have spent the morning trying to catch a Lake Emerald—a dragonfly that, like me, calls the cold, deep, bottle-green waters of Found Lake home.

A pause.

“What do you do when you catch them?”

This second question invariably follows the first.

“Just release them.” When most people hear me say this they raise their eyebrows and add “Well—have fun!”.

I look over my shoulder in the direction of this person to add “they’re very beautiful”, but they are leaving.

Pursuing dragonflies at Found Lake.

I am not a fisherman, but I have to imagine there are parallels between angling and pursuing dragonflies. Part of the experience is about the place, part of it the chase, and much of the rest the quarry itself. So here I am at Found Lake, submerged to my waist, with keen eyes on the dragonflies around me. I have been watching a male Lake Emerald coursing back and forth over a patch of water just out of my reach. Many dragonflies seem to have an uncanny ability to fly just beyond the maximum extent of my swing—even if I try to conceal the extent of my reach by drawing my arms in at the elbows. This dragonfly remains loyal to his patch of water where it is too deep for me to net him. I give up and slosh back towards shore. Before I get there, a Lake Darner rattles by on its big, clear wings. They are not so wary as the Lake Emerald, and I nab him with a sluggish, one-armed swing. I reach down into the bag of my net and immobilize the insect by gently pinching its wings together. Unlike a butterfly or moth, this does no damage and is the most appropriate way to hold a dragonfly. I lift him out and admire the multi-dimensional blues and greens in his eyes, the mosaic-pattern on his thorax and abdomen. Even though I have his wings immobilized, he is trying to fly by working his flight muscles. His body vibrates. I spend a moment more studying this impressive insect, and then separate my thumb and forefinger which I had been using to pinch his wings together. He is off and away into the blue sky.

Lake Darners (Aeshna eremita) are impressive beasts. Males patrol the shores of Found Lake in late summer looking for food and mates.

This place was my summertime home for nine years while I worked for the park service as a naturalist. At first, I took up accommodation in the dormitory-like house which sits on a forested hill above the lake. Later, I came to stay in an ancient, five-room trailer that was annexed to the main house by a wooden deck. My room was on the end of the trailer—“Room 1”—and it came to feel like home in spite of its mousy scent and minimalist décor. Indeed, at every year’s return, I would savour the sight and smell of that little room. I still do.

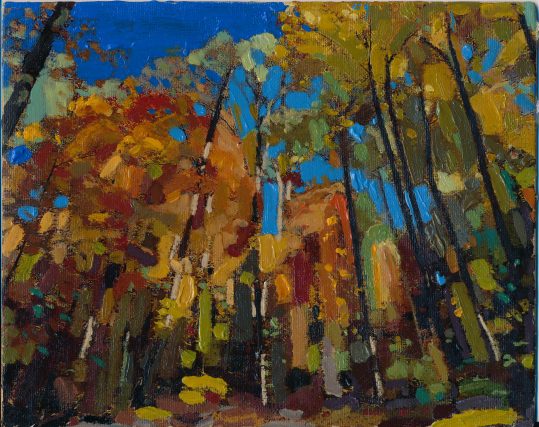

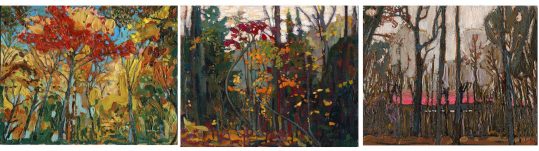

I wander up a familiar little path that winds through the woods, connecting the shoreline to the yard. I ditch the net in my room and saunter first out to the yard, and then in to the woods that enclose the house and the tiny clearing it sits in. My feet follow along a big, old, rotting grandfather log I found a Red-backed Salamander nest in last year. This is the way I experience this place now—relived memories of my deep history with these woods; I saw this here once; did this there; felt that way at that time. I lift my eyes from the log and look up to study the canopy above. The autumn colour show is slow to flush this year and most leaves are still on the trees. I have tried (and always failed) to paint a dense canopy from within the woods. There is something too complex about this ceiling of leaves for my brushwork. A little later on once the leaves are largely down, big windows to the sky open up and it is easier for me to capture how it feels to stand before all this light and colour and sky.

As the leaves begin to fall in autumn, big windows to the sky open up and painting the woods becomes a celebration of blue sky and the colour of Algonquin’s hardwoods.

It makes me smile to think of what is ahead. I am always taken with how autumn turns from soft at the outset, to beautiful, then melancholy as the leaves drop. By late October what had been so warm and lavish comes off as cruel and gothic. Autumn’s outset is so conventionally beautiful but its end is dreadfully so. The drama is fabulous.

And as is so often the case, I end up thinking about executing paintings during my ramblings. I am drawn to scenes that I can successfully render by blending lyrical and literal elements. I use these two things to gauge my work…two far in one direction, not enough in the other. I think this hybrid approach constrains me within a zone where I demand of myself both a unique interpretation of the scene but also technical competency. What precisely is that colour on the water?; how do branch angles differ between red and white pines?; is there a message about my impression in this painting?; are my observations banal? Indeed, the struggle is always to separate my preconception from what is actually before me. It is all too easy to see only what we expect—that clouds are white, that water is blue, that tree bark is brown. It is a true challenge to demand truth of your eyes and see beyond these preconceptions. I fill the afternoon wandering and thinking about colours, tones, and The Great Autumn Spectacle these woods put on every year.

And as is so often the case, I end up thinking about executing paintings during my ramblings. I am drawn to scenes that I can successfully render by blending lyrical and literal elements. I use these two things to gauge my work…two far in one direction, not enough in the other. I think this hybrid approach constrains me within a zone where I demand of myself both a unique interpretation of the scene but also technical competency. What precisely is that colour on the water?; how do branch angles differ between red and white pines?; is there a message about my impression in this painting?; are my observations banal? Indeed, the struggle is always to separate my preconception from what is actually before me. It is all too easy to see only what we expect—that clouds are white, that water is blue, that tree bark is brown. It is a true challenge to demand truth of your eyes and see beyond these preconceptions. I fill the afternoon wandering and thinking about colours, tones, and The Great Autumn Spectacle these woods put on every year.

It is late evening now and I add some finishing touches to a painting I started this afternoon. Sometimes it is like this—that I become aware I have missed some detail, or the image lacks a particular colour only hours or days after I have done it. Even so, as I rework some small details on this piece tonight I still find myself unhappy with it. I find that as I work on a painting it exudes its future, be it good or bad. Sometimes I keep going in spite of a poor forecast, but these ones rarely work out and I paint over them or break them anyways. In the end, my judgment of a painting is always binary—did I succeed, or should I destroy this? I probably destroy more than half of what I do. This particular painting is not going where I want it to, so I accept what I already knew and draw my biggest brush across it to smear what I have done. Time for a break. I slide the painting away from me and put my dirty brushes in a jar of water so the paint doesn’t get crusty and ruin the bristles. Turning around, I flick the light off and slip out of my trailer into the night, shutting the door behind me.

A pack of wolves has spent most of the fall around a meadow not too far from the house. By late summer the pups are too large to be confined to the narrow, underground dens they were born in, yet too inexperienced or undisciplined to accompany adults on hunting forays. As such, the pups are often left in a meadow while the adults make hunting expeditions to feed their pack. Sometimes a given meadow is used by the pack as a rendezvous site for weeks. I get in my car and head that direction—I feel like an adventure before bed. Maybe I will see a wolf on the road, or get the pack to respond if I

howl with my own voice. Excitement aside, I go slow. Working in Algonquin has left me with a real fear of colliding with moose at night—which is catastrophic for both parties and can be easier to do than one might picture. A moose is a huge animal, but its long spindly legs seem to lift most of that mass up and out of one’s headlights so that they are almost impossible to see. Night-driving on Highway 60 is now a 70-kilometres-per-hour-white-knuckle-affair. The road is dead and I pass no one on my way to the site where I suspect there could be wolves.

I arrive, pull over on to the shoulder, and step out. I let the night and the silence gather back around me. At first the car ticks and sighs, but eventually grows quiet. It is warm. Katydids—relatives of grasshoppers and crickets—give off mating songs in lispy, broken hisses. It is still. Overhead, moonlit ash-gray clouds slide slowly, slowly across the sky. Once I feel like the noise and light I must have brought to the scene as I drove here has been absorbed by the night, I suck a deep breath in and bring cupped hands to my mouth. I let out a long steady howl. My position as a Park Naturalist gifted me lots of time to practise an imitation wolf howl because it was our responsibility to locate packs leading up to Algonquin’s famous Thursday night Public Wolf Howls. When I was younger I know that I strove for loud howls, which I bastardized by wailing as loud and as long as I could at the pitch of an ambulance siren. This would work, but given more time and a keen ear I now opt for a lower-pitched howl that is shorter, softer, and more of a wavering wail. Much like how painting demands more truth of your eyes—seeing past the preconceptions that clouds are white, that sky is blue—listening to a true wolf howl with open ears really does reveal it is not much like the cliché “AWOOOoooooooo” we think it is. I listen. Even at the best of times and with the best of howls, getting a successful response is rare simply because wolves are distributed so thinly across the Algonquin landscape. That is why I start, and then grin, when I hear a howl rising from the woods just in from the road. A wolf chorus almost always starts with a single animal breaking the silence [a dominant older individual?], which is followed by what I presume are younger animals. Tonight’s response is no exception, and within a few seconds the night is a single, harmonized wolf song. It feels almost funny to hear such a thing standing with my hands in my pockets on the dark, empty highway. I crane my ears. How many animals? It is always fewer than it sounds. While I can imagine that the group is twenty-strong, I suspect it is probably three or four. After what is probably almost a full minute of howling, the group stops.

While I was park staff one of the most common questions I got about wolves from the public was whether or not a pack would aggressively approach me while scouting for the Public Wolf Howl—”since you are in their territory”, they would add. My response to this was always “no”, having had heard so many responses without ever having any approach me.

Giving the weekly Wolf Talk at Algonquin’s Outdoor Amphitheatre was a highlight of my time working there.

Standing on the quiet highway, I hear a rustling grow louder and louder from about where my ears figured the wolves were howling from. A few moments more and it is very apparent at least two (or is it three?) animals are trotting my direction. It occurs to me that all the fallen autumn leaves make any movement in the woods far louder than it would ever be in the summer, and so with a few inches of dry, crunchy leaves on the forest floor I am privy to what is going on around me in the dark. Perhaps these leaves are revealing to me what I had wrong for all those years, and that wolves do regularly make an approach to investigate an unfamiliar howl. I stand still, occasionally picking up rustlings here and there, and once a whine that sounds just like an anxious dog. I presume these wolves can see or smell me and are both curious and frightened of this thing that smells and looks like a man, but moments ago sounded like a wolf. Slowly, I pull a light out of my pocket, lift it to my eyes, point it down the highway, and click it on. The beam falls directly on a wolf standing on the shoulder perhaps 70 or 80 metres away. I can only barely make it out, but its silver-green eyeshine registers clearly. Even its body language suggests an anxious curiosity, which I feel I can read by the two points of eyeshine alone; the head drops, moves from side to side—the wolf shuffles to one side to change its perspective, and then looks back at me…all the same things a person would do if tasked with discerning some shape in darkness. Perceiving such a relatable state of mind in this wolf makes sharing this landscape with it all the more special. I click off my light and go home.

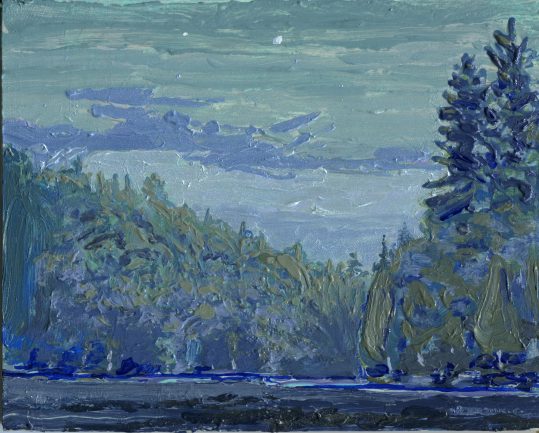

Back at the house, I step out of the car and scan the scene before me, cataloguing what colours the night is wearing. Basil, one of the naturalists, has a white sheet hung on the wall of the house that he has illuminated with a light to attract moths—his entomological muse. The light bounces off the sheet and casts a cold blue-white glare on most of the scene before me. I look to the sky and make the assessment that it is navy—or is it really a green? I find the colours of night particularly hard to identify. Are there colours there at all? Before calling the night finished, I pad down the laneway to the Art Centre’s parking lot which sits at the shore of the lake. I have always loved walking at night—an activity I relished all the more when I encountered the word nemophilist while reading. At that time it was unfamiliar to me so I looked it up.

nemophilist (noun)

* a haunter of the woods

In the moonlight the pavement is like a big silvery dish. I can stand in the middle of it and watch the moon and the clouds and the water. My eyes adjust to the darkness as I leave Basil’s light behind and I gradually find it easier to discern what is around me, easier to become the nemophilist. There is the lake—a sliver of light below dark hills which form the horizon. I go to the shore and stand where a break in the trees leaves the lake framed before me. I study the pared-down nocturne—how simplified everything is. A lot of what I try to do in my paintings is remove detail to convey a clearer message, a stronger image. In life, moonlight does that work for me; I get to walk around and live in the landscape I seek to create. I love the idea of being able to come back to haunt the moonlit shores of Found Lake forever. Too bad I don’t believe in ghosts. I step out of a moon beam in to a shadow, pass through it, and emerge back in to a slant of silvery light. I look up at the sky. What is that damn colour? Maybe some mixture of silver and cobalt teal would be right. I might try that later. My immortality may just

depend on these details. I will never truly become the Found Lake phantom, but this nemophilist’s paintings just might. If I can get this right—if I can capture the image, snare the colours, and express the feeling—then I can haunt my audience long after I have left : ” yes; that’s right—I have seen it like that—I felt that way too”.