Artists in Algonquin Park – Past and Present (part one)

Artists in Algonquin Park – Past and Present (Part One)

By: Joel Irwin

I ) The Past

In May of 1912, two men arrived in Algonquin Provincial Park by train with fishing rods, camping gear, and paint boxes in hand. They took up residence at Camp Mowat on Canoe Lake and began to vigorously sketch the surrounding landscape. One man was Harry B. Jackson, a Toronto artist and graphic designer, and the other was a young and ambitious outdoorsman who would later become Canada’s most famous painter – his name was Tom Thomson.

These artists traveled 220 km on the Grand Trunk Railway from Toronto, where they both worked at Grip Limited, a leading commercial design firm. Among Thomson’s coworkers were J.E.H. Macdonald, Arthur Lismer, Frederick Varley, Frank Johnston and Franklin Carmichael, all of whom would later be members of the Group of Seven painters. Although designers by trade, these young men were artists by heart and all entertained notions of developing a school of art that would awaken a new Canadian consciousness and identity.

Their subject–– the vast and unknown North country, which had haunted the early Canadian imagination as a place of mystery and danger. Stories abounded about people freezing, drowning, or going mad in the Northern wilderness. The fatal end of arctic explorer John Franklin, who was said to have eaten his own boots out of starvation, became the stuff of popular legend. Artists too had died while traveling into the North – landscape painter Neil Mckechnie drowned at 27 on the Mattagami River. The Canadian North was at the time a mythic landscape, and its dangers and mysteries fascinated the Toronto painters, who believed they could discover there not only new subjects, but new artistic styles.

The Algonquin School of Painters

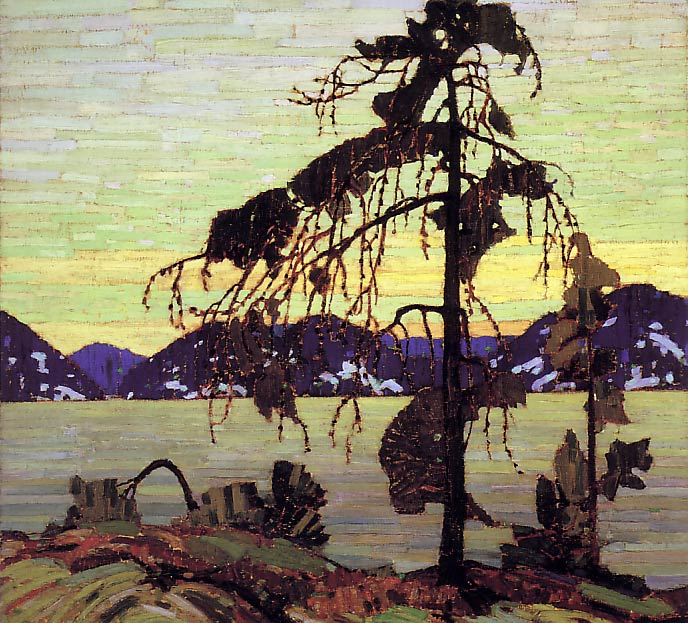

Algonquin Provincial Park, a protected wilderness just north of Toronto would provide the ideal location for the painters to realize their aspirations. The Toronto artists began to follow Thomson into the Park to sketch and paint its granite outcrops, windblown pines, and its various lakes and rivers. Joining them was A.Y. Jackson, a talented Quebec artist, and Lawren Harris, a wealthy and educated painter, both of whom brought to the group an intellectual and spiritual interest in art that would add an air of legitimacy and depth to the burgeoning school. Their years in Algonquin were prolific ones, and the landscape would inspire some of Canada’s most famous paintings, such as Thomson’s “Jack Pine” and A.Y. Jackson’s “Red Maple.” Algonquin Park had become a cradle for a new art movement, and its artists became known in the media as the “Algonquin School of Painters.”

The Algonquin School exhibited their works at various galleries and art shows, and although their experimental styles met with much criticism, they gradually garnered public support, and many of their works were purchased by the Art Gallery of Ontario and the National Gallery. Their works promoted the idea of an art form native to the Canadian landscape—an idea of particular appeal for Canada at the time, as it was still in the early stages of developing a distinct, cultural identity. These painters’ adventurous trips into the wilderness represented a new kind of artist, who embodied the adventurous spirit of the nation—bold, daring, and inspired by the Canadian frontier. They reflected too a desire for a world outside modern, industrial society, a world untouched by the “machine” as Thomson would call it.

The rise of the industrial age was the force behind a number of art movements in Europe, the most famous being “modernism”, where artists challenged traditional, conservative aesthetics to create new, individualistic expressions of the world. The Algonquin School was not untouched by these movements, since almost every member had trained or studied art in Europe. A.Y. Jackson described post- impressionist painters Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Cézanne as gods, and J.E.H.

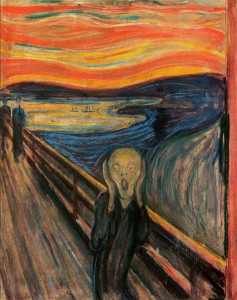

Macdonald, the de facto leader of the Algonquin school, praised the mystical qualities of Norwegian expressionist painter Edvard Munch: “He aims to paint the soul of things,” Macdonald would say, “the inner feeling rather than the outward form….” Macdonald saw in Munch’s landscapes not representations of things, but expressions of mental states – an idea of significant influence for Macdonald and his peers, especially Lawren Harris, whose interest in spiritualism and theosophy would begin to influence his compositions.

Tom Thomson

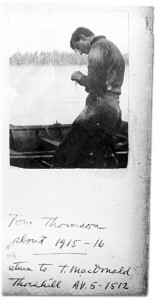

Tom Thomson was the only artist in the Algonquin school who did not train or study in Europe. His intense love for the Canadian North set him apart from the other members of the group. His art production was tied to the seasons, as he would spend the winter living in a shack outside a Toronto studio, waiting impatiently for the ice to break so he could return to his beloved Algonquin and paint its spring, summer, and fall.

Thomson shared with Algonquin Park something that no other artist could share. It was his inspiration, his muse, and he would spend as much time there as was possible. It was in Algonquin where Thomson developed his signature style. Mixing principles of graphic design with a bold application of colour, Thomson achieved something wholly new. Snow, trees, and water became the central elements of his work, which he would accentuate through quick and controlled brush strokes.

The Algonquin landscape offered Thomson infinite possibilities of design, its wilderness consisting of spaces crisscrossed with verticals and diagonals—patterns which undoubtedly appealed to the young painter’s imagination. Thomson had found his muse and was quick to share it with his fellow Toronto artists, who would, in turn, help Thomson refine his style by teaching him the finer points of composition and colour. In this way, Thomson was acquainted with the larger ideas and art movements in Europe. A.Y. Jackson would later say in his biography that Thomson “would tell me about canoe trips, wildlife, fishing, things about which I knew nothing… . In turn,

I would talk to him about Europe, the art schools, famous paintings I had seen and the Impressionist school which I admired.” This it seems was the basis of Thomson’s art education. As he led the Toronto artists into more remote parts of Algonquin, they would lead him to more refined realizations of his art. Thomson then was both the best student and the most successful practitioner of the Algonquin School of painters.

The Mystery of Tom Thomson

On July 16th, 1917, the body of Tom Thomson was found floating in Canoe lake, Algonquin Park. Although the official cause was declared death by drowning, speculations of foul play began to circulate among the CanoeLake community. Speculations soon turned into rumours, and rumours into steadfast convictions. Who killed Tom Thomson has obsessed Canadians for decades, and his death has become one of Canada’s great mysteries, being the subject of films, novels,

songs, and even the “Tom Thomson Murder Mystery” board game. The whereabouts of his body has also become a mystery. Although he was originally buried in a small graveyard on Canoe Lake, his body was believed to have been exhumed and moved to Owen Sound for burial, although some recent scholars have challenged this claim and argue that his body still lies in an unmarked grave on Canoe Lake. Whatever the truth, the mystery of Tom Thomson has fascinated Canadians for over a century. Some have even claimed to have seen his ghost, paddling quietly through the mist – a clear sign of his enduring presence in Algonquin Park.

Sources: Ross King, “Defiant Spirits”; Roy MacGregor, “Northern Light: The Enduring Mystery of Tom Thomson”; Joan Murray, “Tom Thomson: The Last Spring”; Ottelyn Addison, “Tom Thomson: The Algonquin Years”; A.Y. Jackson, “A Painter’s Country”